Iryna Kaminska, Andrew Meldrum and Chris Young

Since March 2009, UK long term rates have moved around a lot – as shown in Figure 1 – despite Bank Rate being held fixed. To understand these movements you need to understand term premia. In this blog, we suggest that much of the movement in term premia reflects global factors.

Figure 1: UK 10-year nominal government bond yield, January 2009 – May 2015

Sources: Bloomberg and Bank of England

A 10-year government bond yield can be split into two components: investors’ expectations of the average short-term monetary policy rate over the next 10 years; and a ‘term premium’, defined as the additional compensation investors demand to hold a longer-term bond relative to a series of shorter-term bonds. Consider an investor with a one-month investment horizon. She can buy a one-month (default-free) bond, which offers a certain return in one month. Alternatively, she can buy a 10-year bond and sell it in one month’s time. The price of a 10-year bond in one month is uncertain, so the return on this strategy is uncertain, even if the 10-year bond is free of default risk. If the investor is risk averse, she will require a risk or ‘term’ premium to hold long-term bonds relative to short-term bonds.

Term premia matter: they are an important influence on the borrowing rates faced by governments, households and companies. Central banks need to monitor and understand movements in long-term interest rates when assessing the overall stance of monetary policy And term premia contain useful information, for example about market participants’ uncertainty about future interest rates and their attitudes to risk.

Estimating term premia

As it is not possible to observe term premia directly, they need to be estimated using a model of bond yields. But, as with any economic model, there is substantial uncertainty involved. We use a range of different models to estimate term premia.

Most of our term structure models derive from the ‘affine term structure model’ (ATSM) of Duffee (2002). In these models, bond yields are modelled as functions of a small number of variables, or ‘pricing factors’. We can use these models to produce forecasts of future interest rates, including the short-term policy rate. The term premium can be computed as the difference between bond yields and the model forecast of the average expected policy rate.

Our models include simple ATSMs, assuming that the pricing factors are given by unobserved variables or principal components extracted from observed bond yields; a joint model of the yields on both nominal and index-linked government bonds; a model that incorporates macroeconomic variables as pricing factors; and a joint model of the yields on both UK and US nominal government bonds. We also use a shadow rate version of the model, imposing that the short-term interest rate has to remain above zero or another lower bound.

Estimates of the UK 10-year term premium from our models since May 1997 – when the Bank of England obtained operational independence for monetary policy – are presented in the swathe in Figure 2. The dark blue line shows the mean estimate across the models and the light blue shading shows the range of estimates. This swathe illustrates the substantial uncertainty around term premium estimates.

Figure 2: Swathe of estimates of the UK 10-year term premium, May 1997 to March 2015

Source: Bank of England

Interpreting movements in UK term premia

Movements in the UK term premium over time provide an insight into how they are determined – and the role of domestic and global factors. There are four key episodes to highlight.

First, changes to the UK monetary policy regime in the 1990s. In October 1992, the UK adopted an inflation targeting framework for monetary policy and in May 1997 the Bank of England was given operational independence with monetary policy set by the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC). Meldrum and Malik (2014) note that gilt yields drifted downwards steadily during the 1980s and that there were sharper falls following the changes in October 1992 and May 1997. Consistent with these changes, Guimaraes (2012) finds that there were particularly large falls in the component of the term premium that compensates investors for uncertainty about future inflation rates (the ‘inflation risk premium’) during the 1990s. Other UK-specific factors have been important too. For example, the Minimum Funding Requirement became effective in April 1997 and led to increased pension fund demand for index-linked bonds, contributing to a fall in the UK term premium, as discussed in Joyce, Kaminska, and Lildholdt (2012).

Second, the build up to the global financial crisis. This period was associated with decreased risk aversion and compressed pricing of risk across financial markets, including the pricing of interest rate risk reflected in the fall in the term premium.

Third, the global financial crisis and the monetary policy response to it. At the height of the crisis in 2008-9 term premia rose sharply: despite a flight to quality out of risky assets and into government bonds, investors demanded additional compensation for interest rate risk. In response to the crisis, policymakers around the world took action, including loosening monetary policy by lowering interest rates and quantitative easing. Purchases of UK government bonds as part of the MPC’s quantitative easing programme may have compressed term premia; Joyce, Mclaren and Young (2012) review the evidence.

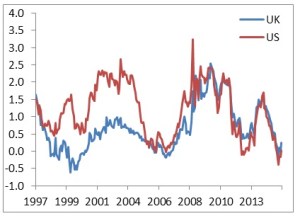

Figure 3: Estimates of the UK and US 10-year term premium, May 1997 to April 2015

Source: Bank of England, NYFed

Fourth, changing market expectations over the course of 2013 about the Federal Reserve ‘tapering’ its quantitative easing programme. Figure 3 shows estimates of 10-year premia for the UK and US, estimated using the Adrian, Crump, and Moench (2013) approach. The sharp rise in both the UK and US term premium from the spring of 2013 and subsequent falls are striking.

Figure 3 also highlights the close co-movement of UK and US term premia more generally, particularly since 2009. This suggests that common global factors are important determinants of the term premium or that there are international spillovers between financial markets.

Moreover, euro area – as well as US – developments influence UK term premia. The sharpest falls in term premia since 2009 took place between the summer of 2011 and the first few months of 2012. This coincided with a period in which concerns about the outlook in the euro area intensified, which may have led to increased demand for safe assets such as government bonds and compressed the term premium. The anticipation and announcement of the ECB’s Public Sector Purchase Programme (PSPP) in the first quarter of 2015 may have contributed to the compression in term premia in the both UK and US over this period.

Conclusion

Term premia are a key component of changes in long-term interest rates.

Some of the changes in UK term premia reflect domestic factors, for instance changes in the UK’s monetary policy regime. But, in a small open economy such as the UK, global factors are an important influence. Given the increasing global integration of financial markets, a significant proportion of the movements in UK term premia depend on changes in global risk sentiment and global uncertainty, and on monetary policy developments in the US and euro area. Looking forward, one of the challenges to UK monetary policy is that prospective monetary policy tightening in the United States or an intensification of geopolitical tensions triggers a marked reappraisal of risk in financial markets internationally and hence a sharp increase in UK term premia.

Authors: Iryna Kaminska, Andrew Meldrum and Chris Young work in the Bank’s Macro-Financial Analysis Division.

Bank Underground is a blog for Bank of England staff to share views that challenge – or support – prevailing policy orthodoxies. The views expressed here are those of the authors, and are not necessarily those of the Bank of England, or its policy committees.

If you want to get in touch, please email us at bankunderground@bankofengland.co.uk