Thomas Mathae, Stephen Millard, Tairi Room, Ladislav Wintr and Robert Wyszynski

How do firms respond to shocks? Do they first change the hours worked by their employees? Or the number of employees? Or wages? Or a combination? Does the shock matter? And the firm’s country? One way of answering these questions is to ask the managers within firms themselves. And this is exactly what the Wage Dynamics Network did, surveying firms in 25 European countries. Our research used this survey to answer these questions. We found that in response to negative shocks firms were most likely to reduce employment, then wages and then hours, regardless of the source of the shock. But, in response to positive shocks, firms were most likely to raise wages, then employment and then hours.

Macroeconomic background

The Great Recession that followed the financial crisis of 2007-2008 resulted in a large fall in output and a rise in unemployment across Europe. The subsequent experiences of different countries varied considerably, as some countries saw a recovery in economic growth, while other countries continued to see stagnant, or even declining, output.

But even for countries experiencing GDP drops of similar magnitude the labour market responses differed. For example, in 2008-2009 real wages, employment and hours all fell in Latvia, whereas in Lithuania real wages and employment were reduced and in Estonia employment and hours were cut). The question is, do these differences result from different shocks in the countries, different timing of the shocks, different labour market institutions across countries, or different responses over time. By using survey data, we are able to isolate the responses of firms to each shock in each country.

How do firms respond to shocks in theory?

To help us understand how firms might use different methods of adjusting their labour costs, we developed a simple theoretical framework in which firms decide how to respond to shocks based on the relative costs of adjusting hours, employment or wages. We show that firms will adjust labour costs in the cheapest possible way, and that the decision will be the same, whatever the source of the shock. The model also implies that adjustment can be asymmetric in response to positive versus negative shocks, if decreasing wages, employment or hours is more costly for firms than increasing these variables or vice versa.

The Wage Dynamics Network survey

To examine how firms respond to shocks in practice, we used results from the third WDN survey of EU firms. The survey covers about 25,000 firms in 25 countries and was carried out in 2014-2015. It included firms in the manufacturing, construction, wholesale and retail trade, and business and financial services sectors. The aim of the survey was to collect information on how firms set wages generally, together with how they set their labour input and wages in response to the shocks that have been affecting them over the recent years. The core time period under investigation was 2010-2013, the period of the European sovereign debt crisis. A subset of countries also asked questions for the period 2008-2009, the initial phase of the economic and financial crisis.

The questionnaire collected firm characteristics as well as qualitative views on economic shocks and firms’ adjustment responses. Firms were split into five size buckets: 1-4 employees, 5-19 employees, 20-49 employees, 50-199 employees and 200+ employees. Firms were asked how their activity was affected by the level of demand, access to external financing and the availability of supplies from the firm’s usual suppliers, together with how they adjusted various components of their labour costs in response to these shocks.

To show that the survey answers can be linked to macroeconomic outcomes at the country level, in Figure 1 we plot the changes in total labour costs (ie, wage bill), hourly real wages, employment and hours for each country over the periods 2010-13 (red line) and 2008-09 (blue line) against the weighted net balances of firms in the survey which stated that they adjusted their labour costs along each of these margins in each of these periods. The positive correlation between the macroeconomic data and the survey balances in all cases except average hours in 2010-13, suggests that analysing firm responses to shocks can help us understand macroeconomic developments.

Figure 1 shows that the regularities coming from macroeconomic data are also apparent in the survey responses. First, the deep recession in the Baltic countries and Ireland in the Great Recession period of 2008-2009 is clear. The fall in employment, wages and hours compares with ongoing increases in wages and total labour costs on balance in other EU countries. Second, during 2010-2013 the deep recessions in Greece and Cyprus are reflected by the substantial reductions in total labour cost, employment and wages.

Figure 1: Labour cost changes across countries: relationship between firm-level survey responses and aggregate measures

How did EU firms respond to recent shocks?

Figure 2 shows

the relationship between labour costs and their components and demand shocks in

the 25 countries surveyed over 2010-13 (red line) and the 8 countries surveyed

over 2008-09 (blue line). We can see

that permanent and temporary employment are much more likely to be reduced in response to negative shocks

than base wages.

Figure 2: Response of labour costs to a demand shock

To examine the determinants of different channels for adjusting labour costs in response to shocks, we adopted a three-step approach. In step 1, we ran multinomial logit models to examine what determined the probability of adopting each of eight adjustment strategies: no adjustment, adjusting only wages, only hours, only employment, wages and hours, wages and employment, hours and employment, and, finally, adjusting all three. The explanatory variables included dummies for each of the shocks (with positive and negative shocks considered separately), sector dummies and firm size dummies. In step 2, we use these estimates to calculate the predicted probability of adjusting via each of the eight margins. And finally in step 3, we aggregate the probabilities of each of these adjustment strategies in order to rank the probabilities of adjusting employment, wages and hours for each shock and country.

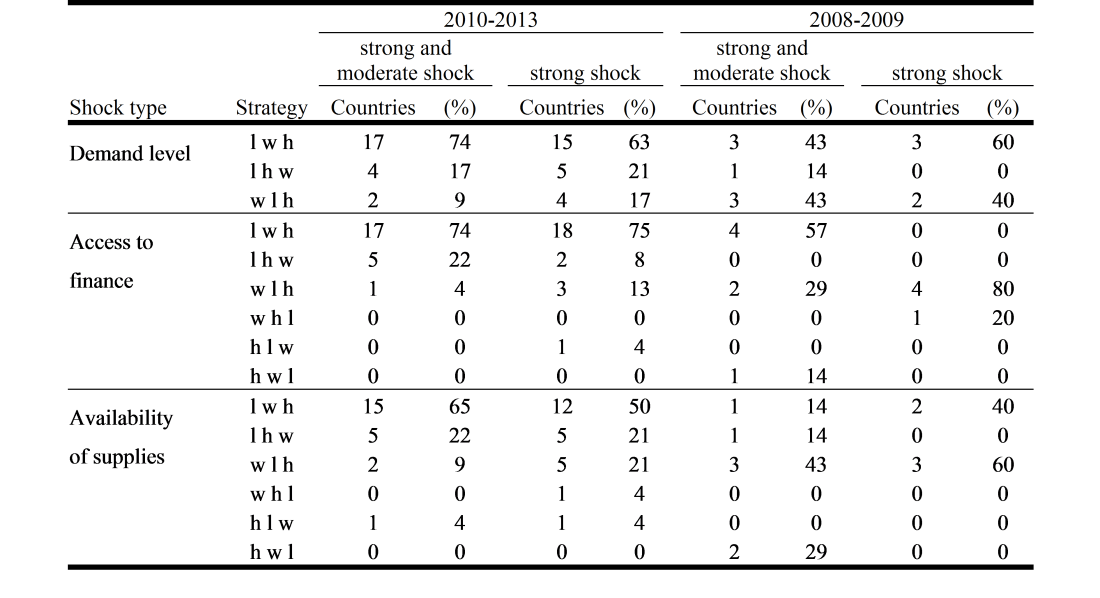

Table 1: Labour market responses to different negative shocks

Notes: l, w and h refer to employment, wages and hours, respectively. The three alternatives are ordered such that predicted probability of reducing the first variable is greater than the probability of reducing the second variable, which is greater than the probability of reducing the third variable. Malta is excluded due to a small number of observations. Countries for which the multinomial logit model was not reliably estimated (no convergence, determined outcomes) are excluded. Ties between strategies are split. The percentages might not sum to 100% due to rounding.

Source: WDN3 data, own estimations.

Table 1 presents, for each type of negative shock, the number and share of countries for which the given adjustment ranking was the most common. In 2010-2013 the dominant adjustment pattern was ‘labour–wages–hours’, meaning that cutting employment had the highest predicted probability in most countries, cutting wages the second and cutting hours ranked last. The second most commonly observed ranking was ‘labour–hours–wages’, implying that cutting employment was the most likely response to a negative shock, independently of the type of the shock or the country in our sample. In terms of the simple model we developed, this suggests that the costs of adjusting employment downwards are smaller than the costs of adjusting either wages or hours downwards.

To investigate the role of labour market institutions, we split the countries in the sample according to their level of employment protection legislation (EPL), centralisation of wage bargaining and coordination of wage bargaining. We found that high levels of employment protection legislation (ie, those countries above the median level of EPL according to the OECD’s index of EPL) made it less likely that firms reduced wages when facing negative shocks. We also found that countries with decentralised and/or fragmented wage bargaining systems adjust via wage cuts and are less likely to reduce employment after a negative shock while the opposite is true for more centralised and/or coordinated bargaining institutions.

We also investigated the adjustment strategies followed by firms facing positive shocks. We found that the most common adjustment strategy after a positive shock, independent of shock and period, was ‘wages–labour–hours’, meaning that firms in most countries were most likely to increase wages in response to a positive shock, the employment and then hours.

Conclusions

How do firms respond to shocks? For positive shocks, they are most likely to raise wages, then employment and then hours, regardless of the source of the shock. In response to negative shocks, they first reduce employment, then wages and then hours. But, in times of strong economic decline, such as in the 2008-09 period, or when faced by strong negative demand shocks, firms were more likely to cut wages. These findings imply that nominal wages tend to be downward rigid, but this rigidity is relaxed in deep recessions.

Thomas Mathae works for the Central Bank of Luxembourg, Stephen Millard works in the Bank’s Structural Economics Division, Tairi Room works for the Bank of Estonia, Ladislav Wintr works for the Central Bank of Luxembourg and Robert Wyszynski works for the National Bank of Poland.

If you want to get in touch, please email us at bankunderground@bankofengland.co.uk or leave a comment below.

Comments will only appear once approved by a moderator, and are only published where a full name is supplied. Bank Underground is a blog for Bank of England staff to share views that challenge – or support – prevailing policy orthodoxies. The views expressed here are those of the authors, and are not necessarily those of the Bank of England, or its policy committees.