Jeremy Franklin, May Rostom & Gregory Thwaites.

In the aftermath of the 2007/8 financial crisis bank lending to firms fell back sharply and investment plummeted. And at the same time, growth in labour productivity and wages fell, with neither fully recovering since (Chart 1). Are these facts causally linked, and if so, in which direction? Did firms stop borrowing because they had no good uses for the money, or did banks cut lending, making it harder for firms to do business? In a new paper, we find a way to distinguish between the two. We measure how changes in the amount firms were able to borrow affected how much they invested, how much their workers produced and earned, and how likely firms were to survive.

We find that the effects are sizable, at least over the first two years of the crisis. A 10% fall in the amount a firm can borrow reduced capital per worker by around 5-6%, labour productivity by 5-8% and wages by 7-9%. We also find that firms facing adverse credit conditions were more likely to fail, with a 10% decrease in credit supply increasing the probability of bankruptcy by around 60%.

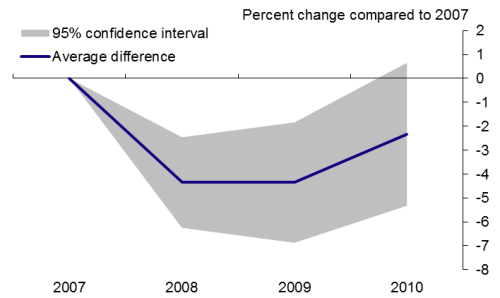

If you combine our results with an estimate of how much of the fall in firms’ borrowing was due to changes in credit supply, it is possible to explain a large slice of the fall in investment and productivity. Suppose, for the sake of argument, that half of the fall in the amount firms borrowed was due to less credit supplied by banks, and half because they demanded less from banks (recent research by Barnett and Thomas has in fact suggested that the majority of the initial fall in UK aggregate lending was due to credit supply shocks). Then out of the 17% fall in labour productivity relative to trend by 2013, maybe one third to one half would have been because of tighter credit supply (Chart 2). Similarly, this might explain half of the 60% increase in insolvencies between 2007 and 2009.

Chart 1: Bank credit, investment, labour productivity and real wages

Source: ONS, Author calculations.

Chart 2: Estimate of the impact of credit supply on labour productivity

Source: ONS, Author calculations. Notes: The pre-crisis trend is calculated between 1997Q1 and 2007Q2. The grey swathe assumes that 50% of the deviation in PNFC bank credit relative to trend was due to changes in credit supply. The upper bound for the impact on productivity uses an elasticity of 8% and the lower bound 5%, based on the estimates in Franklin, Rostom and Thwaites (2015).

Identifying changes in credit supply

To produce our estimates, we put together a large sample of UK firms using company accounts data. As well as recording firms’ investment, productivity, and employment, we are also able to identify any party that has a claim on a firm’s assets – usually as collateral for a loan. In most cases, these parties are banks, and will be the main bank that the firm in question does its banking with.

Our ability to identify the effects of changes in credit supply derives from two key features of the data. First, firms tend to stick with borrowing from the same bank, at least over short periods of time. And second, banks faced similar borrowing costs before the crisis but fared very differently afterwards. Chart 3 shows a measure of wholesale borrowing costs for the largest UK lenders. After the onset of the crisis, borrowing costs went up for all banks, but they went up by different degrees. So while credit was readily available to firms at comparable rates across banks before the crisis, banks’ subsequent ability to extend credit to firms varied markedly.

Chart 3: UK bank CDS spreads

Source: MarkIT, authors calculations. The chart shows the five year senior Credit Default Swap (CDS) premia across four of the largest UK banks and is used here as a proxy for wholesale funding costs. Further details are available in Beau, Hill, Hussain and Nixon (2014).

The combination of these two factors means that firms faced very different credit conditions after the crisis simply because of whom they had happened to choose to bank with before the crisis struck. So comparing changes in total borrowing after the crisis for firms with different pre-crisis banking relationships allows us to identify the effect of the change in the supply of credit on outcomes after the crisis hit – without having to worry that we are capturing changes in firms’ demand for credit, or changes in wider demand conditions, instead. Our approach follows in a similar spirit to Bentolila et al (2013) for Spain, Chodorow-Reich (2014) for the US and Paravisini et al (2015) for Peru.

Now it could be that total borrowing by firms differed across banks for reasons other than credit supply, or firms themselves caused their banks to get into difficulties. This would mean that our estimates would not only be picking up the effect of differences in credit supply, but also the effect of these other factors. With this in mind, we show that firms banking with different banks were indeed the same on average before the crisis, except for their banking relationships and a small set of other things we can control for. Moreover, we show that the main cause of the banks’ problems lay outside the UK corporate sector (apart from the commercial real estate sector, which we exclude from our sample). This allows us to be confident that a firm’s pre-crisis banking relationship will just pick up the effects of changes in credit supply and not any of these other factors.

To illustrate this point, think of two firms that are identical in every respect except for their banking relationships. Their banks subsequently experienced different funding shocks. Because these two firms are identical on all other fronts, any variation in total borrowing by each firm must be due to changes in the amount of credit supplied by those banks. And any differences in firm outcomes, such as productivity growth or investment, should also be the result of changes in credit availability.

Charts 4 and 5 help demonstrate this. Chart 4 shows the average difference in total debt growth between two groups of firms in our sample – those with relationships with relatively strong banks and those with relatively weak banks – controlling for other observable characteristics. Chart 5 shows the difference in productivity growth between these two groups of firms. They show that both debt and productivity grew significantly less quickly for those firms whose banks cut lending by more.

Chart 4: Average difference in total debt growth among firms with relationships to ‘weaker’ banks

Source: Authors calculations. Notes: The chart shows the coefficient on a dummy variable indicating that a firm has a relationship with a ‘weak’ bank in a regression of firm debt and other controls for each year. A bank or institution is defined as ‘weak’ if average debt growth among firms it had a relationship with in 2008 and 2009 lies below the median institution.

Chart 5: Average difference in productivity growth among firms with relationships to weaker banks

Source: Authors calculations. Notes: The chart shows the coefficient on a dummy variable indicating that a firm has a relationship with a ‘weak’ bank in a regression of firm productivity (defined here as turnover per head) and other controls. A bank or institution is defined as ‘weak’ if average debt growth among firms it had a relationship with in 2008 and 2009 lies below the median institution.

Credit supply and productivity

Why should changes in credit supply affect productivity? We argue that the increased difficulty in obtaining finance led firms to reduce investment and hence the capital intensity of their production. With less capital available per worker, the productivity of their workforce is likely to have decreased relative to other firms.

Since the capital share of income is around a third, we would usually expect the impact on productivity to be a third of the size of the impact on capital intensity. However, our estimates suggest that the impact of credit on productivity is larger than implied by this channel alone. There are several possible explanations. The remainder could be attributable to reduced use of other inputs or intermediate goods, which may also be paid for on credit, or the diversion of time towards the management of firms’ cashflow. Lower credit supply may also be associated with lower levels of innovation and technological development, all of which may have contributed to weaker productivity growth among affected firms.

Conclusion

Our research suggests that the credit crunch after the financial crisis is likely to have had a large impact on the supply-side of the UK economy, at least in the short-term.

But relationships between firms and banks do decay over time – as firms switch banks and loans are paid off. This means our method tells us less about what the longer-term impact of the credit shock is likely to be. It could be that firms are somehow permanently scarred, or it could be that they are able to catch up lost ground once more normal rates of lending growth resume. These remain important questions for assessing the longer-term growth prospects of the economy.

Jeremy Franklin and May Rostom work in the Bank’s Monetary Analysis Division and Gregory Thwaites works in the Bank’s Global Spillovers and Interconnections Division.

If you want to get in touch, please email us at bankunderground@bankofengland.co.uk. You are also welcome to leave a comment below. Comments are moderated and will not appear until they have been approved.

Bank Underground is a blog for Bank of England staff to share views that challenge – or support – prevailing policy orthodoxies. The views expressed here are those of the authors, and are not necessarily those of the Bank of England, or its policy committees.

Nice research paper, key issue, excellent review of previous research in the Bank staff working paper. But I suspect the credit supply effects are overestimated for the following reason. The weak banks, notably RBS, were I think willing to supply credit to comparatively high risk borrowers with more cyclical business models and lesser ability to service loans. Post crisis their borrowers were likely to perform worse than borrowers of other banks regardless of any constraints in loan supply.

the key question is whether the firm level variables used adequately control for business cycle risk and business model. The control variables used in the staff working paper (2-digit industry sector; whether the firm is a subsidiary, a parent company or a standalone firm; the log level of turnover in 2007, and firm age in 2007 at time t.) are not sufficient for this task. One would wish to include also e,g, growth of turnover 2005-2007; interest cover. I think this can appear in a good journal , but if the reviewers do their job they will wish to see robustness testing, including additional firm level control variables along these lines.

Alistair Milne, Loughborough University