Yuliya Baranova, Carsten Jung and Joseph Noss.

There has been a recent increase in awareness of investors that limiting emissions to prevent climate change might leave a substantial proportion of the world’s carbon reserves unusable, and that this could lead to revaluations across a range of financial assets. If risks are left unaddressed, this could result in large losses for some investors. But is this adjustment in financial market prices likely to be abrupt? And – even if it is – is it likely to pose risks to financial stability? We argue that the answer to both these questions could be yes: financial valuations can move sharply even if the transition to sustainable energy were smooth. And exposures are sufficiently large to warrant attention from both investors and policymakers.

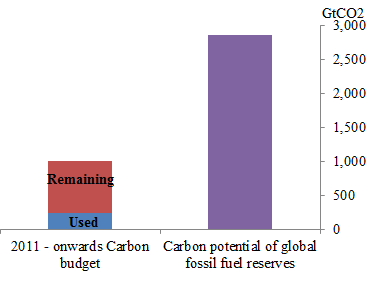

As part of the recent Paris agreement, world leaders have committed to limit the rise in global average temperatures relative to those in the pre-industrial world to 2˚C, and to pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5˚C. Underpinning the Paris Agreement is a recognition that further emissions of greenhouse gases should not exceed a remaining ‘carbon budget’, which according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate change, amounts to 1000 gigatonnes of CO2 emissions from 2011 onwards (roughly a quarter of which will be used up by the end of the year (Chart 1)).

Analysis by the International Energy Agency suggests that remaining within the 2˚C limit, will necessitate reasonably swift changes in capital allocation and investment. Global demand for oil and coal will need to peak by as early as 2020. There will need to be $16 trillion less investment in fossil fuel related assets compared to business as usual by 2040; and $24tn more investment needs to go into renewables and efficient energy usage. Such a sweeping reallocation of capital naturally brings with it risks to financial stability. Firms whose business plans are least in line with these transition scenarios may suffer as a result of the transition; others, including those who have undertaken investment in alternative energy, might benefit.

Chart 1: Global carbon budget vs carbon potential of global fossil fuel reserves

Source: IPCC, Carbon Tracker and Bank of England. Used refers to an estimate as of end-2016.

Research on the exact nature and size of such ‘transition risks’ is in an early stage. For example, a recent Bank Underground column found that, historically, news of investors’ concerns around firms’ carbon exposures had a negative – but statistically insignificant – impact on the value of energy companies.

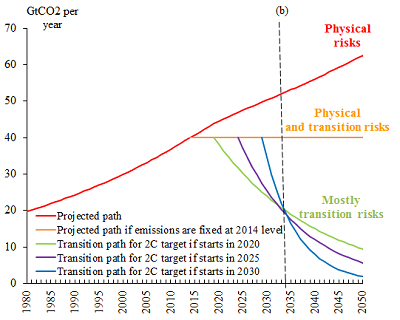

But the value of financial market securities linked to carbon emissions could deteriorate more abruptly in future, particularly once the Paris Agreement and associated national legislation are in place. This could be triggered by a continuation of the recent increase in losses linked to climatic events (Chart 2), or growing perceptions on the part of investors that policymakers are taking concrete actions to achieve the transition to a low carbon economy. Once this shift in expectations of future profits occurs, valuations can shift abruptly. According to one estimate, 80% of energy firms’ equity valuations depend on cash flows further than 5 years in the future. So, even if the energy transition kicks in only by 2020, it could have a large impact on today’s valuations.

Chart 2: Recent insurance loss events worldwide, 1980-2014(a)

Source: Munich Re.

(a) ‘Loss event’ refers to the risk that a single event, or series of events, leads to a significant deviation in actual claims from the total expected claims, usually over a short period of time (often 72 hours).

(b) Earthquake, tsunami, volcanic activity. (c) Tropical storm, convective storm, local storm. (d) Flood, mass movement. (e) Extreme temperature, drought, forest fire.

Large movements in prices may not, in themselves, impair financial stability. But risks might arise if a sharp repricing was to occur in several sectors simultaneously (say, oil & gas, utilities, automobiles, materials) or if this were to spark further sales by investors and affected the availability of finance for firms more broadly. A sharp repricing of assets might also adversely impact the balance sheets of banks and other financial institutions via their holdings of affected securities (as our colleagues have argued). It’s therefore little wonder that transition risks associated with climate change have recently caught the attention of policymakers.

To assess the possible impact on financial markets of a transition to a low carbon economy on financial markets we first need to consider a scenario for future carbon emissions. Some stylised examples are shown in Chart 3:

Chart 3: Possible trajectories of carbon emissions(a)

Source: IPCC, World Energy Outlook (WEO) 2013 and Bank calculation.

(a) Historical growth rate in carbon emission is inferred from 1970-2013 average; forward growth rates are as per WEO 2013 projections and fixed at 2035 level after.

(b) Timing at which the carbon budget will be exhausted should emissions be fixed at the current level (as per orange line).

The red line shows carbon emissions continuing on their current trajectory. Whilst this could lead to all sorts of climate-related risks in the long-run, it’s benign in its implications for the transitional risks considered here. The green line shows a scenario in which carbon emissions are fixed at their current level, before – as a result of policy-maker action – reducing from 2020, at a rate consistent with meeting the 2 ˚C target. The blue line shows how, were that transition to begin later, in 2030, faster transition is required to stay within the target.

To estimate the potential impact on financial markets, we then identify types of industries that would be affected to different degrees by a limit on carbon emissions: both ‘first-tier’ – companies that will be impacted directly by such limits on their ability to produce fossil fuels (these include global coal/oil/gas companies and energy utilities); along with a wider set of ‘second-tier’ energy-intensive companies that will be affected indirectly via an increase in energy costs. Together, these account for around 28% of global equity market capitalisation (Chart 4).

To explore the potential magnitude of re-pricing of energy stocks, we conduct a simple thought experiment. This begins by making the assumption that investors base current energy stock valuations on an assumption that these firms’ earnings – and hence, dividends – will rise by 2% per annum. We then suppose that instead, as a result of the crystallisation of transition risk, these firms’ dividends begin to fall by 5% per year, starting in 2020, to approach zero in 2050 (consistent with the shallower transition path denoted by the green line in Chart 3). Under that simple scenario – combined with the assumption that the compensation investors require for taking risk on equities remains constant at around its long-run average – we estimate that affected firms’ equities would lose around 40% of their value, equivalent to a fall of around 11% in global equity market capitalisation (although this might be partly offset by gains in sectors benefitting from transition). This shows how even a smooth transition path could result in abrupt re-pricing.

If such a repricing were to take place reasonably rapidly, as we have argued it could, it might have the potential to entail risks to financial stability. And, historically, equity price changes of this size have sometimes been associated with shocks affecting the wider economy, not least given the impact they have on individuals’ wealth.

Chart 4: Amount of global equity and fixed-income assets at risk(a)

Source: Reuters, Datastream, Dealogic, Bloomberg and Bank of England calculations.

(a) Numbers on the bars show value of assets at risk, expressed in US$ trn.

Chart 5: Debt service ratios for major energy companies

Source: Moody’s Analytics and Bank of England.

(a)Balance sheet data used are as adjusted by Moody’s analysts.

Turning to credit markets: together, first-tier and second-tier companies account for roughly 31% of the global traded credit outstanding (three right-hand bars in Chart 4). In 2013, interest coverage ratios – that is, the ratio of earnings to interest payments – for most of the world’s largest energy companies were higher than ten (Chart 5), suggesting that their earnings would likely be sufficient to service interest payments on their existing debt even in the case of a significant fall in revenues. That said, following the fall in the oil prices during 2014/15, these ratios deteriorated materially.

If the shock to revenues/profits were permanent – as might be the case under the crystallisation of climate transition risks that posed a longer-term risk to the viability of some firms – a rise in refinancing costs could ultimately result in an increase in defaults (as affected firms were unable to roll-over their debts), with associated implications for financial stability. Indeed, roughly 60% of public debt issued by oil and gas companies matures after 2020 and, thus, could be impacted by transition risks. Reflecting this, some credit ratings agencies have started taking climate-related risks into account in making their rating decisions.

The impact of transition risks would likely be substantially reduced were the transition to begin early. Public policy may play a role in ensuring this. For example, the G20 Green Finance Study Group has outlined how signals from policymakers could help provide more clarity on what path the transition to green energy might take.

In addition, better disclosure of firms’ climate-related risks and opportunities could help smooth price adjustments. That’s because, if information is available early on, investors can start early to align their portfolios with climate targets. This, in turn, prevents capital misallocation and ultimately reduces the risk of a later – and thus more abrupt – adjustment. In other words, bringing the adjustment forward will reduce financial stability risk.

A step change in this regard has just come from the FSB Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD): this private-sector group has just published wide-ranging recommendations for better reporting of firms’ climate risks. They will apply to all sectors, ranging from energy firms to institutional investors. Financial firms with $20trillion in assets have already announced their support. These guidelines, if implemented widely, may help kick-start the market mechanisms that are needed to align capital allocation with climate targets and thus help “creating a market in the transition” (Carney, 2016).

Yuliya Baranova and Joseph Noss work in the Bank’s Capital Markets Division and Carsten Jung works in the Bank’s Policy and Strategy Division.

If you want to get in touch, please email us at bankunderground@bankofengland.co.uk or leave a comment below.

Comments will only appear once approved by a moderator, and are only published where a full name is supplied.

Bank Underground is a blog for Bank of England staff to share views that challenge – or support – prevailing policy orthodoxies. The views expressed here are those of the authors, and are not necessarily those of the Bank of England, or its policy committees.

Fascinating article. Is there a danger that firms in other countries (such as China) will steal a march on the USA and the UK, and continue to invest heavily in new low-carbon technology, whilst we reduce our investment?

Arguably the reasonably rapid reallocation of financial resources away from fossil fuels and toward cleaner energy will mean greater consolidation in the industry, at least initially. The greatest financial risk comes from a revaluation of oil and gas reserves and that will proceed from the basins with the highest total carbon intensity (including E&P, processing and transport to market) to the lowest. Concentrated portfolios are more likely to be affected to the point of threatening the viability of the companies owning them (watch out for ownership interests by private equity investors!), allowing the larger players to acquire the viable reserves of defaulting companies. The largest companies have options including a switch to cleaner energy; the very large investments required for the eventual switch to a sustainable energy system force a long enough timeline that the risks matter more for equity investors (where revaluaton of reserves leads to permanent loss of value) than for creditors (where revaluation leads to temporary losses through higher credit spreads but is unlikely to lead to permanent losses as credit exposure tends to be relatively short term). Bond investors are perhaps in the most difficult situation as the maturities are much longer, leaving them more exposed to the risk of actual loss.

The prospect of an orderly transition such as the 5%pa dividend decline suggested here is very limited. To meet the CO2 emission targets it is essential that transport emissions are drastically reduced which can only be done through a wholesale move to electric vehicles. This will lead to a decline in the demand for oil which is likely to precipitate a sharp decline in price. Producers will not cut supply if they anticipate the decline persisting; indeed the incentive will be to produce as much as possible before demand disappears completely.

As EV’s become the norm, automotive manufacturers will cease to produce fossil fuel powered vehicles, so accelerating the decline in oil demand. Oil companies will thus suffer a significant fall in revenues over a very short time-frame, rather than a steady reduction. High cost production areas will have to be abandoned (at significant cost) and companies focused on such projects, such as tar sands players, will quickly go into receivership.