Marco Bardoscia, Paolo Barucca, Adam Brinley Codd and John Hill

The failure of Lehman Brothers on 15 September 2008 sent shockwaves around the world. But the losses at Lehman Brothers were only the start of the problem. The price of their bonds halved, almost overnight. Other institutions that held Lehman’s debt faced huge losses, and markets feared that those losses could trigger further failures. The good news is that our latest research suggests that risks within the UK banking system from one such contagion channel, “solvency contagion”, have declined sharply since 2008. We have developed a new model which quantifies risk from this channel, and helps us understand why it has fallen. Regulators are using the model to monitor this particular source of risk as part of the Bank’s annual concurrent stress test exercise.

In our model, when a bank loses money, it becomes less likely to pay back its creditors. This means the creditors reduce the value of their claims, because they are less sure of being repaid. The initial loss spreads from one bank to another in this way, through the network of debt exposures. Therefore, the model allows us to capture the potential for an initial shock to be amplified by connections between banks.

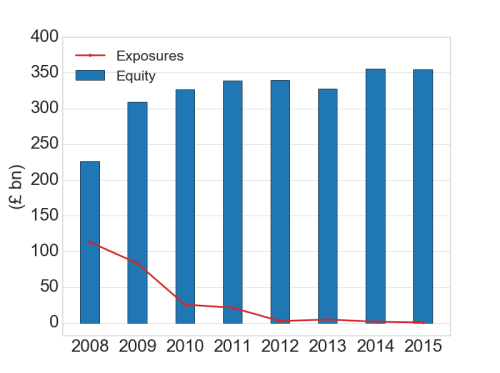

Chart 1 shows how banks increased their equity reserves, and limited their exposures to each other in the wake of the crisis. The banks in sample are the banks currently part of the Bank of England annual concurrent stress test (Barclays, HSBC, Lloyds, Royal Bank of Scotland, Nationwide, Santander UK, and Standard Chartered). The exposures include direct lending to other banks, holdings of other banks’ debt instruments, and exposures on derivatives. The extra equity makes banks more resilient by making them better able to absorb losses, and limiting exposures helps by reducing the interconnections through which contagion spreads. We use our model to quantify how important these changes were in limiting this particular source of contagion risk.

The model tells us about ‘solvency contagion losses’. These are the losses which happen when banks reduce the value of their claims on each other.

The purple bars in Chart 2 show the sharp fall in ‘contagion losses’ amongst UK banks, after they have suffered some initial loss. The other bars decompose the changes in these losses through time into the key drivers: changes in equity (blue); changes in exposures (red); and an unexplained residual (yellow). We find that, increasing amounts of total equity and falling total exposures drive almost all of the reduction in contagion losses.

Zooming in on the periods 2009-2010 (left panel) and 2011-2012 (right panel) in Chart 2, we notice one particularly striking result. Over these periods, total equity (shown in Chart 1) in the banking system was either rising, or broadly constant. But the blue bars in Chart 2 suggest that this was contributing to an increase in solvency contagion losses. On the face of it, this doesn’t make sense – equity acts as a buffer against losses, protecting the value of debt claims following a shock. But this result highlights an important point – looking only at system-wide numbers can mask the detailed complexity that gives rise to systemic risk. While total equity was rising in one case, and or broadly unchanged in the other, the distribution of equity and exposures across the banks was changing in a way which made the solvency contagion losses worse. Those changes more than offset the good news present at the system-wide level.

Using models like these is a crucial step towards treating the financial system as more than the sum of its parts. Looking at banks one at a time can miss out important ‘macro-dynamics’ that arise from how they interact with each other. Those interactions can be powerful sources of systemic risk. Developing network models of the financial system is a step towards building stress tests that are more truly macro-prudential.

Marco Bardoscia, Adam Brinley Codd and John Hill work in the Bank’s Stress Testing Strategy Division.

Paolo Barucca works at the University of Zurich, London Institute for Mathematical Sciences.

If you want to get in touch, please email us at bankunderground@bankofengland.co.uk or leave a comment below.

Comments will only appear once approved by a moderator, and are only published where a full name is supplied.

Bank Underground is a blog for Bank of England staff to share views that challenge – or support – prevailing policy orthodoxies. The views expressed here are those of the authors, and are not necessarily those of the Bank of England, or its policy committees.