Philip Bunn, Alice Pugh and Chris Yeates

Following the onset of the financial crisis, the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) cut interest rates to historically low levels and launched a programme of quantitative easing (QE) to support the UK economy. How did this exceptional period of monetary policy affect different households in the UK? Did it increase or decrease inequality? Although existing differences in income and wealth means that the impact in cash terms varied substantially between households, in a recent staff working paper we find that monetary policy had very little impact on relative measures of inequality. Compared to what would have otherwise happened, younger households are estimated to have benefited most from higher income in cash terms, while older households gained more from higher wealth.

What if policy had been unchanged since 2007?

To conduct our analysis, we first need to compute what would have happened if there were no monetary policy loosening. To do this we use the same scenario from the Bank’s main forecasting model, COMPASS, as Carney (2016). In that scenario, GDP would have been 8% lower had monetary policy been left unchanged after 2007, and the unemployment rate 4 percentage points higher. Real asset prices fell over this period, but our scenario implies those falls would have been even larger without monetary loosening: real equity and house prices would have been 25% and 20% lower by 2014 had policy been left unchanged. These simulations should be viewed as purely illustrative rather than definitive, however. In practice, it would have been hard for the MPC to justify that they were meeting their mandate had they kept policy constant throughout the crisis, since their credibility would have been undermined.

How does looser monetary policy affect individual households?

The scenarios reflect the overall economy-wide effects of monetary policy. But to understand how these headline figures feed through to different households we assume monetary policy works via the following channels:

- The cut in Bank Rate reduced household interest payments and receipts, redistributing from savers to borrowers.

- Lower Bank Rate and QE stimulated demand, leading to higher labour incomes as a result of both higher employment and wages.

- Lower Bank Rate and QE boosted the prices of assets such as equities and housing, raising the wealth of households who hold those assets.

- Lower Bank Rate and QE increased the measured value of pensions because they increased the cost of providing those pensions. Note that this may not have ‘felt’ much like an increase in wealth for households, particularly for those with pensions within defined benefit schemes.

- Finally, lower Bank Rate and QE led to higher inflation than would have otherwise been the case. That will have reduced the real value of debt and deposits that were fixed in nominal terms, because a given amount of cash would have bought a smaller quantity of goods and services. We use the aggregate consumption deflator in these calculations.

Using household survey data from the Office for National Statistics’ Wealth and Asset Survey, we estimate how monetary policy affected the income and wealth of a representative sample of households between 2008 and 2014, relative to if policy had been kept unchanged after 2007. As a starting point, we use the estimates for the impact of monetary policy on GDP, employment and asset prices described above and then attempt to map them into the distribution. The effects vary across households depending, for example, on the types of assets that they hold, whether they are borrowers or savers and whether members of the household are in work.

Our key qualitative results largely flow from standard features of the monetary policy transmission mechanism and from the pre-existing distributions of income and wealth. But given the numerous assumptions involved, the direction and relative magnitudes of our quantitative results are as important as the numerical estimates. In addition, our estimates only provide a snapshot of the impact of monetary policy at one point in time. Monetary policy is a short-run tool with a waning influence on the real economy, and hence the effects that we report may diminish beyond our sample period.

Our findings

1. Monetary policy had very little effect on overall inequality

Gini coefficients are the most commonly used summary measures of inequality, providing a single statistic to summarise the relative dispersion of a distribution. We estimate that looser monetary policy only had a small impact on the income and wealth Gini coefficients between 2008 and 2014 (Table 1). That is consistent with the fact that those Gini coefficients were broadly stable in the UK over that period (Chart 1).

Table 1: The effect of monetary policy on inequality*

*Gini coefficients are measured between 0 (perfect equality) and 1 (perfect inequality).

Chart 1: Aggregate measures of inequality*

Sources: IFS and Wealth and Asset Survey.

* Gini coefficients are measured between 0 (perfect equality) and 1 (perfect inequality).

Of course, households had very different levels of income and wealth at the start of this period, and so the estimated effects of monetary policy vary substantially in cash terms across the income and wealth distributions (Chart 2 shows the effects on wealth). But richer households did not gain by more in proportionate terms. Taking wealth as an example, households in the bottom half of the wealth distribution are estimated to have experienced a slightly larger percentage increase in real wealth than those at the top (Chart 3). But it is worth noting that existing differences in net wealth mean that a 10% increase for all would equate to £200 for the bottom decile and £195,000 for the richest.

Chart 2: Effects of monetary policy changes since 2007 on net wealth by wealth decile in cash terms

Chart 3: Effects of monetary policy changes since 2007 on net wealth by wealth decile in percentage terms

2. Younger households have gained more from higher incomes while older households have gained from higher wealth

Since younger households are more likely to include people in work and to have outstanding debts, they have tended to benefit by more than older households from looser monetary policy through higher employment income and lower interest payments (Chart 4). In contrast, older households have tended to lose out from lower savings receipts.

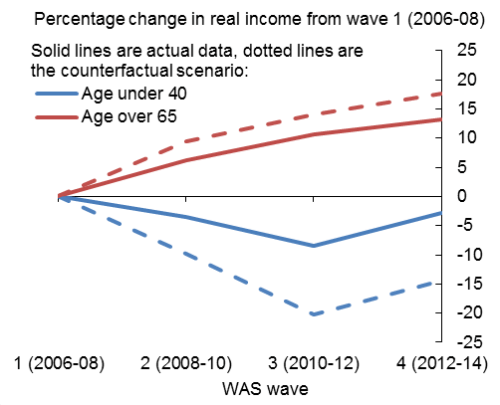

Despite that boost to incomes from monetary policy, however, younger households still did much worse overall during the financial crisis. Chart 5 shows that households where the head was under the age of 40 saw a reduction in their real incomes between 2006-08 and 2012-14, while those aged over 65 saw a rise. Monetary policy merely acted to narrow the gap between these two age groups, as shown by the difference between the dotted lines (our estimates of what would have happened to incomes without monetary policy loosening) and the solid lines.

In contrast to the effect on incomes, older households have benefited most from higher wealth as a result of looser monetary policy, since they are more likely than younger households to hold equities and be homeowners (Chart 4). But since real asset prices fell, these marginal gains just mitigated the extent to which asset holders lost out, rather than making them better off overall.

Chart 4: Effects of monetary policy since 2007 on income and wealth by age

Chart 5: Effects of monetary policy since 2007 on real income by age

3. Changes in monetary policy since 2007 are likely to have made most households better off

Chart 6 shows that, considering only the impact via interest payments and receipts, just over a third of households are estimated to have been made at least £500 better off by monetary policy changes after 2007, with a similar amount having been made worse off. But, once we account for changes in financial wealth and employment income, the proportion made worse off falls to 24%. And after accounting for the boost to housing and pension wealth, only 4% of households are estimated to have been made worse off by looser monetary policy.

Higher housing and pension wealth may not make households feel better off in the way that higher income or having more money in the bank would, however. For example, homeowners who might want to cash in by selling their house still need somewhere to live. In addition, higher house prices increase the cost of future housing, especially for younger households who might want to get onto the housing ladder. Our paper considers this in an extension.

Chart 6: Proportion of households made better or worse off by monetary policy since 2007

Chart 7: Balance of households reporting that they have been made better off as a result of monetary policy

4. Households tend to report that looser monetary policy has made them worse off

In contrast to our findings, the balance of households in the 2017H1 NMG Survey – a biannual survey of households commissioned by the Bank of England – felt that they had been made worse off by lower interest rates since 2008. Those negative responses were concentrated among older households (Chart 7). When asked about the channels through which they had been affected, most focused on the effects on their interest payments and receipts – where older households have tended to lose out – rather than on their wealth.

Conclusion

There has been growing interest in the effects of monetary policy on the distribution of income and wealth. We find that the gains from monetary easing were distributed roughly in line with initial income and wealth holdings. Because the percentage changes in income and wealth were similar across all distributions there was no large impact on inequality. If anything, those at the bottom end of the wealth distribution gained slightly more in percentage terms. Furthermore, most households are estimated to have been made better off than they otherwise would have been if policy had been left unchanged.

Philip Bunn works in the Bank’s Structural Economic Analysis Division, Alice Pugh works in the Bank’s Inflation Report and Intelligence Division and Chris Yeates works in the Bank’s Monetary Analysis and Chief Economist ED Office.

If you want to get in touch, please email us at bankunderground@bankofengland.co.uk or leave a comment below.

Comments will only appear once approved by a moderator, and are only published where a full name is supplied.Bank Underground is a blog for Bank of England staff to share views that challenge – or support – prevailing policy orthodoxies. The views expressed here are those of the authors, and are not necessarily those of the Bank of England, or its policy committees.

I believe that rather than undertaking QE as has been implemented, if the UK Treasury had financed the accumulated deficit over the last 10 years with a mix of roughly half long dated Gilts and half short dated Treasury Bills sold to banks (and continually rolled over), nobody would be having the conversation regarding what effects such a policy would have had. It would just have been the Treasury funding the national debt in a way it saw fit.

The net effect of such a policy would have been more or less identical to the QE that was actually undertaken. New broad money in the form of bank deposits would have been created, banks would have new assets in the form of T-Bills rather than reserves, the central bank’s balance sheet wouldn’t have expanded (not that it makes much difference to anything) and we would have avoided all the silly scaremongering about ‘money printing’ and the money multiplier and you wouldn’t have had to undertaken the research that you’ve just had to do, which most readers are going to disagree with since they have a gut feeling, deep down, that QE must have cost them something somehow.